This article is about the amazing way coral reefs seem to behave as electric ecosystems and provides ideas how this electric side might provide keys as to how to help in saving them.

Text © Sander Funneman, Illustrations © Peter Brouwers

Coral reefs, often called the rainforests of the sea, are crucial for underwater ecosystems. About 65% of the world’s coral reefs is dying, and what is still alive is seriously threatened in its survival. What is going on?

Everywhere, coral reefs are being severely damaged by climate change; by tsunamis, rising sea temperatures, hurricanes, etc. Why is that bad news? Currently, scientists answer that question roughly as follows: a huge diversity of marine plant and animal species depend on coral reefs for their livelihoods. Apart from marine fauna and flora, part of the world’s population also depends on them. This is because coral reefs provide protection from floods and supply fisheries with fish. Coral reefs also play an important role as coastal protection against erosion and in the development of medicines.

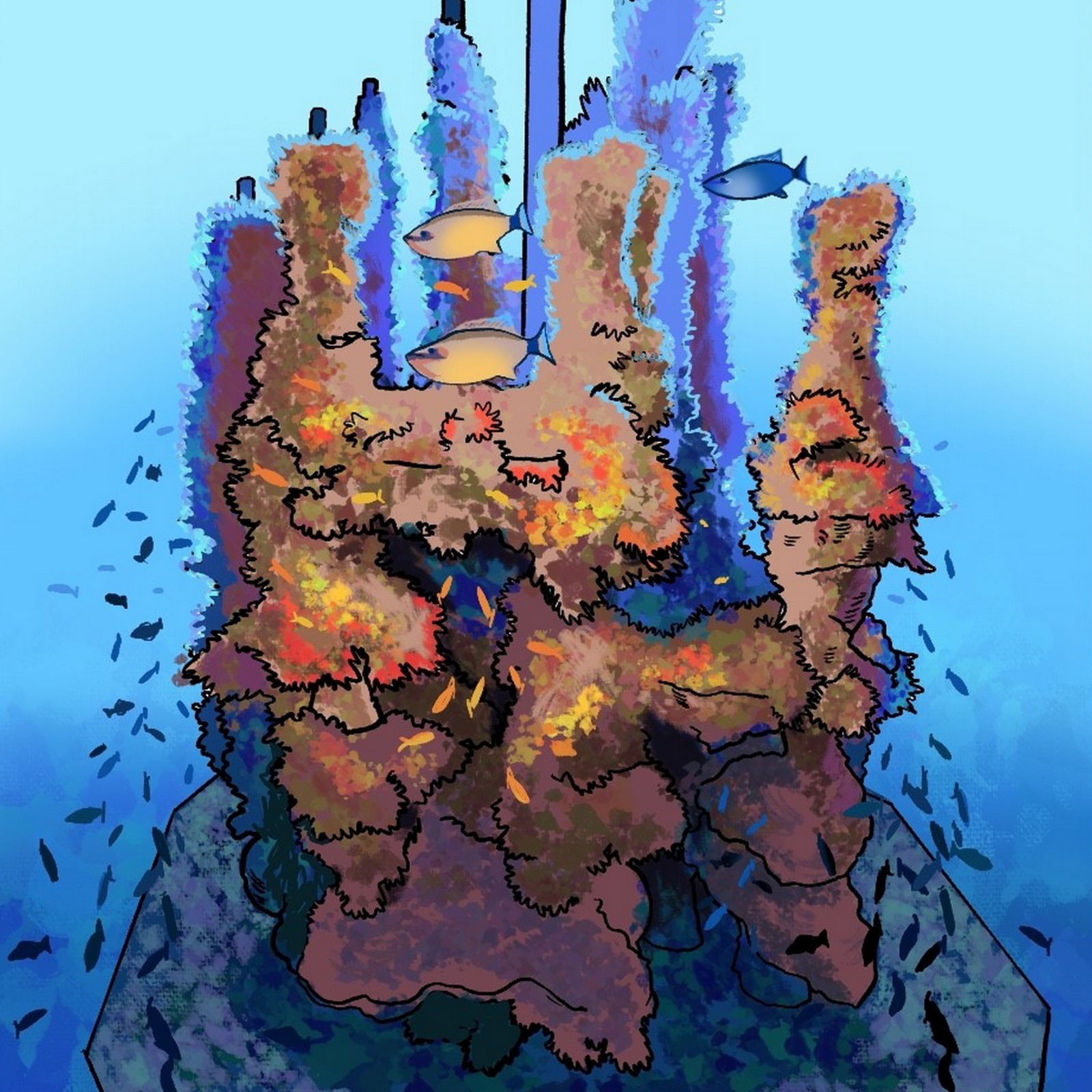

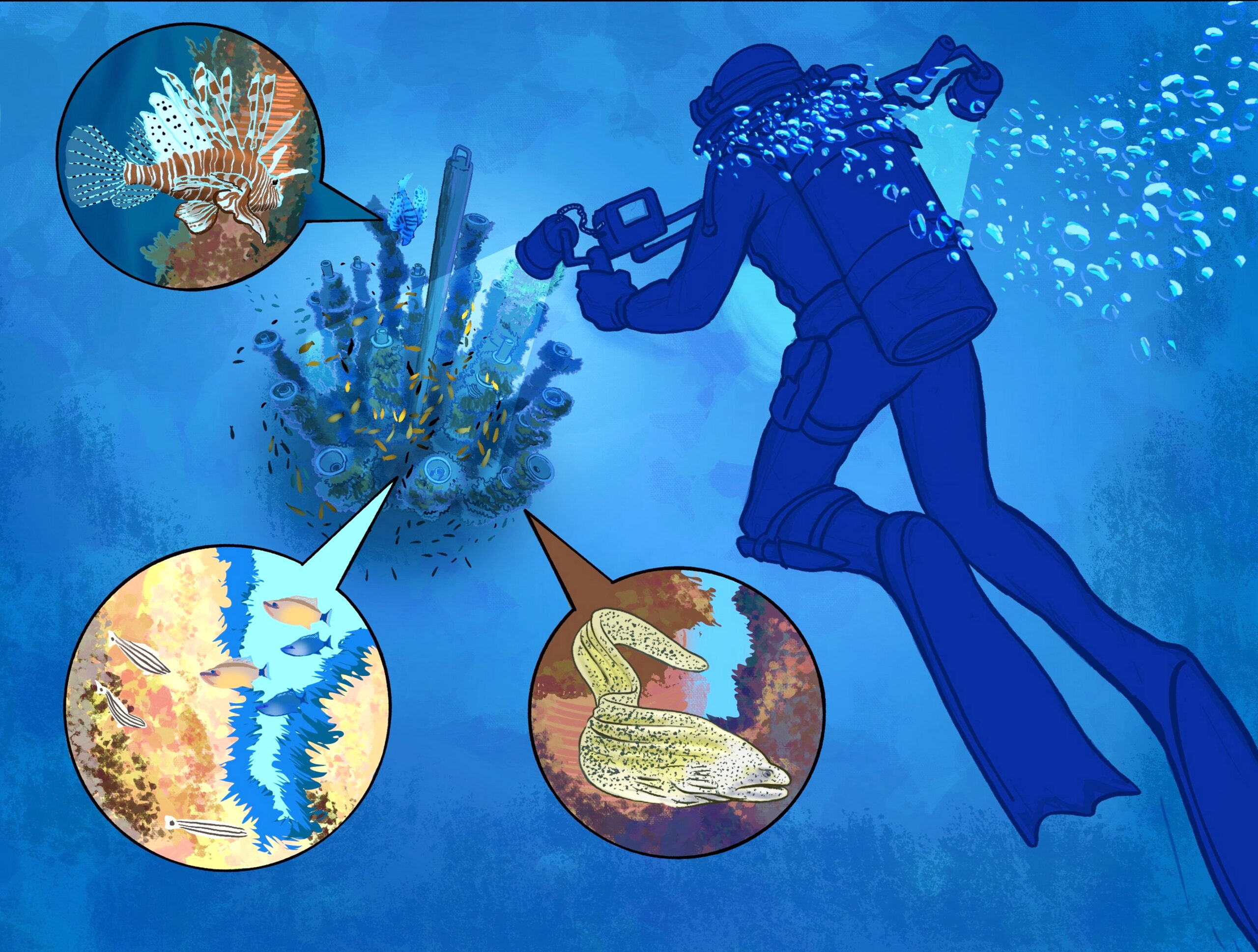

Prof. Ezri Tarazi is an experimental designer and lecturer at Technion University in Haifa. There his research includes 3D printed coral reefs. About a year ago, in spring 2023, Tarazi contacted me. He told that he had placed a metal construction, covered with 3D printed ceramics, off the coast of Eilat in the Red Sea. In nature, coral grows very slowly. However, to his surprise, soft coral settled on the ceramic at an unusual rapid rate and a whole range of reef fish were recruited.

Having no explanation for the speed at which his construction allowed the coral to develop and a wide variety of fish to be recruited, he contacted me. He had read my book Electric Ecosystem and wondered if certain electrical phenomena might play a role. With that inquiry, I went in search of the bioelectric facts.

Coral growth on Tarazi’s construction, within a year of placement.

A few months later, I had lunch with him on a small hill in the middle of a forest in the eastern part of the Netherlands. Surrounded by trees, a clear sky and the light of a warm summer afternoon, we began to put together the puzzle of possible reasons why his construction of steel and ceramics made the coral grow so fast.

Artificial electricity and coral

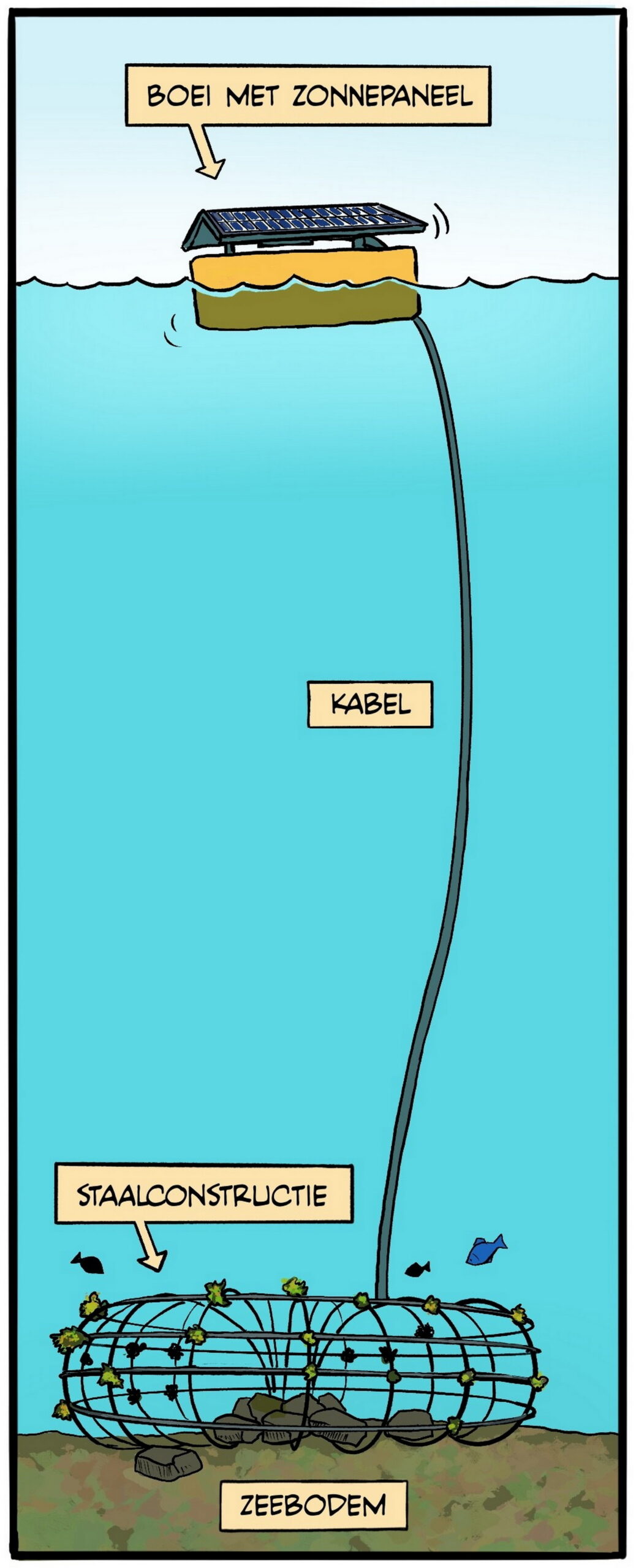

In 1970, Wolf Hilbertz, of the University of Texas, discovered that when an electric current is passed between two metal electrodes in seawater, dissolved minerals are deposited in a layer of limestone. This is similar to the nutrient soil corals need in order to grow. Together with marine scientist Thomas Goreau, Hilbertz used this technique in modified form to create new coral reefs. They named that resulting nutrient medium Biorock. Goreau then led the Global Coral Reef Alliance (GCRA), which has developed more than 700 Biorock reef projects in 45 countries. The GCRA’s new reefs consist of metal structures placed on the sandy bottom. Healthy pieces of live coral, taken from severely damaged reefs, are applied to the metal structures – like cuttings of plants are grafted onto a tree trunk. A time-consuming job. The structures are then electrified, for example via a buoy with a solar panel. The electricity causes a thin layer of calcium carbonate – a main component of limestone – to form around the metal.

Corals easily adhere to this layer and then start growing at an accelerated rate. Normally, coral grows at a rate of a few millimetres a year. With electricity, it now grows much faster. Coral therefore appears to thrive in such an electric circuit and, as a result, seems to be able to be considered an independently functioning electric ecosystem. The technique has already proven itself: in 1998, 95 percent of natural coral reefs near the Maldives died due to coral bleaching, while eighty percent of Biorock reefs survived.

This, of course, seems wonderful news. However, there is a tiny problem. That tiny problem has to do with the word independent in ‘the coral reef as an independently functioning electrical ecosystem’. After all, for this solution, all coral reefs everywhere on earth are becoming increasingly dependent on human-produced electrical power. Currently, coral reefs are thought to cover about 384,300 square kilometres of the ocean floor. That’s almost the area of the Netherlands plus Germany. Therefore, far too large to be completely artificially energized. And although that huge area is still only 0.1% of the seabed, more than 25% of all marine species live there. The conversation with Ezri Tarazi on the hill in the forest took a completely different turn. We not only exchanged about the specific electrical sensitivity of coral reefs, but also about the world’s seas and oceans as fundamentally integrated electrical ecosystems. I shared with him my bioelectrical insights and he brought his practical and experimental knowledge of corals into the conversation.

Bioelectric coral puzzle

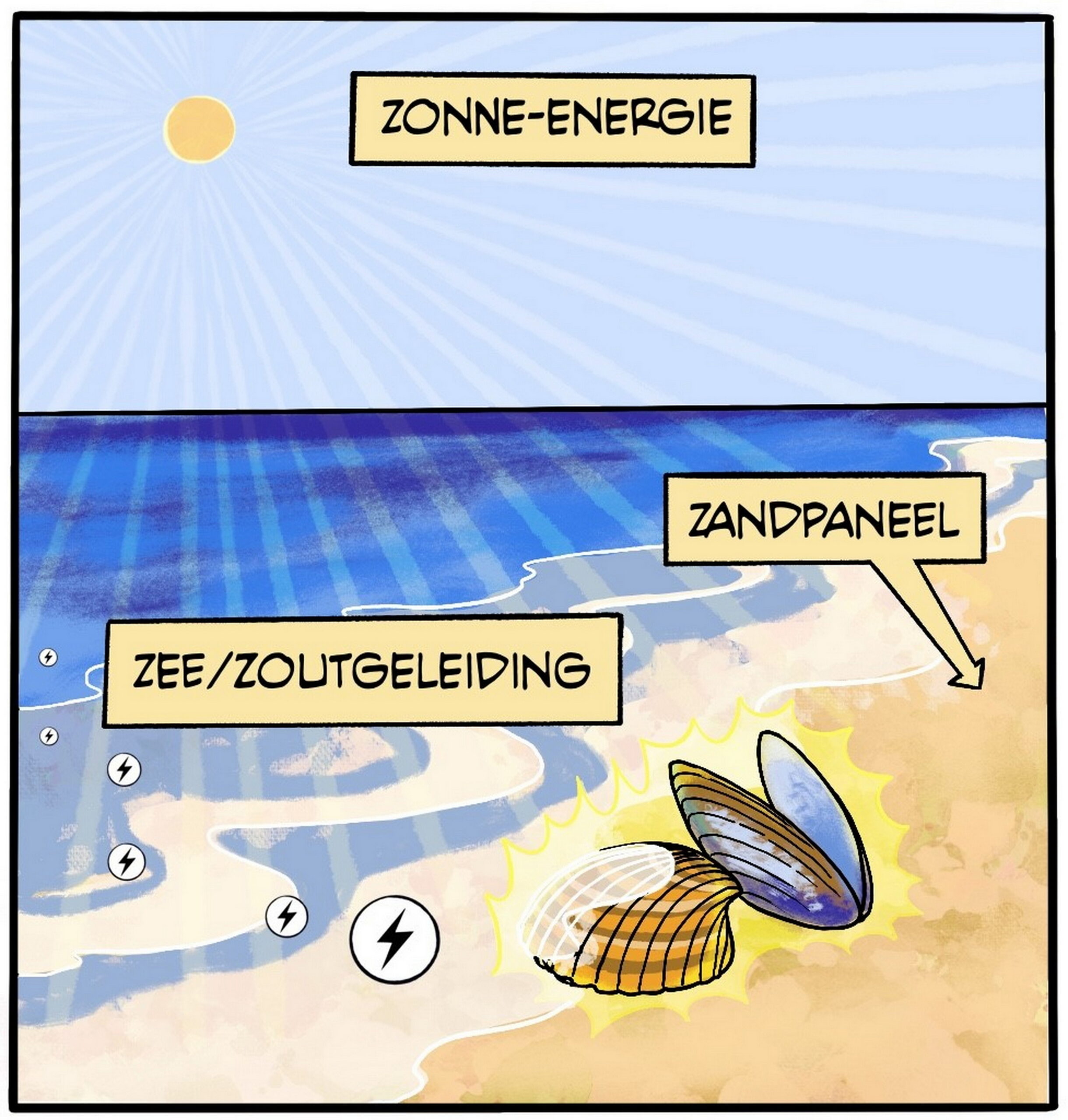

Firstly, under the influence of the moon’s gravity, the tidal movement of seawater, together with the earth’s magnetic field, generates electric currents. The salty ocean water is electrically conductive. These aspects create the basis for a permanent source of natural electricity in the oceans. We then talked about how the mycelium, for example in forest soil, connects trees through bioelectric signals and how plants on the seabed do exactly the same.

We also talked about paramagnetic sand and why shells kept at home remain in perfect condition for decades, while those on the beach disappear in no time. It turns out that to unravel this mystery is not so much found in the power of the surf or the action of the salt water on the shells. The mystery can be unravelled by looking at the electricity; the sand, or silica, turns out to act as a large solar panel that converts sunlight into soil electricity. The regular action of the salty seawater amplifies that effect, because the salt water conducts electricity. And shells are affected by it. It accelerates their degradation process. The electrical charge of the sand and salt water, which washes over the shells at high tide, makes the shells brittle. As it were, in no time the shells melt off the beach to make way for new ones. Thus, pure silica appears to act like a solar panel. Tarazi showed me a photo of the seabed around his construction a few months after installation; to my surprise, it was littered with shell grit.

Coral reef antenna

Tarazi’s construction is located near Eilat, GPS: 29°32’24.5 “N 34°58’11.7 “E. In a radius of more than 3.5 kilometres around the construction, the seabed is barren. Almost nothing grows there and there is little food. Yet, within a few months, a lush coral reef emerged that is now home to all kind of exotic fish, including moray eels and lionfish. How did they get there? How could they find this oasis in the middle of the sea desert?

Scientists are discovering more and more of fish’s electro-receptive abilities. Is that also how fish find their way towards the construction?

Meanwhile, inside the construction the fish species are teeming.

The test assembly, made of natural materials, could well work as an underwater antenna in several ways. The steel antennas, which make up the base of Tarazi’s construction, pick up those natural electromagnetic currents from the salty seawater and channel them through the newly formed coral reef. The design does not require an artificial source of electricity. It allows the reef to maintain its independence and once the construction is in place, no human interference is needed.

The whole thing seems to work like an underwater circuit, with some antennas for reception and conduction. Nothing prevents the natural electric current – generated by the salty water and the earth’s magnetic field – from depositing limestone on the ceramic. The antennas actually function like electrodes in seawater. Thus, the nutrient medium, which corals need to thrive, forms naturally. All the more reason to extend the purely physical approach to coral reefs with a more natural bioelectric approach. Tarazi, with his eco-friendly coral reef antenna, might be on to something very important!

(This article was originally published in Dutch, in Optimist Magazine, nr. 217, July/August 2024)

Sources of Coral Reefs