Everything in nature has a rhythm. In the body this rhythm has a clock. Surprisingly, in the human this clock connects our body to the bigger context of the earth magnetic field

Text © Sander Funneman, Illustrations © Peter Brouwers

Everything in nature has a rhythm. For example, almost the entire population of snow hares in northern Canada disappears every five years, only to expand again in the following five years to more than 600 hares per square kilometre. The peaks and valleys of this population correspond with the 10.5-year solar cycle and the corresponding changes in sunspot activity. When that cycle is intense, the snow hare population becomes extra large.

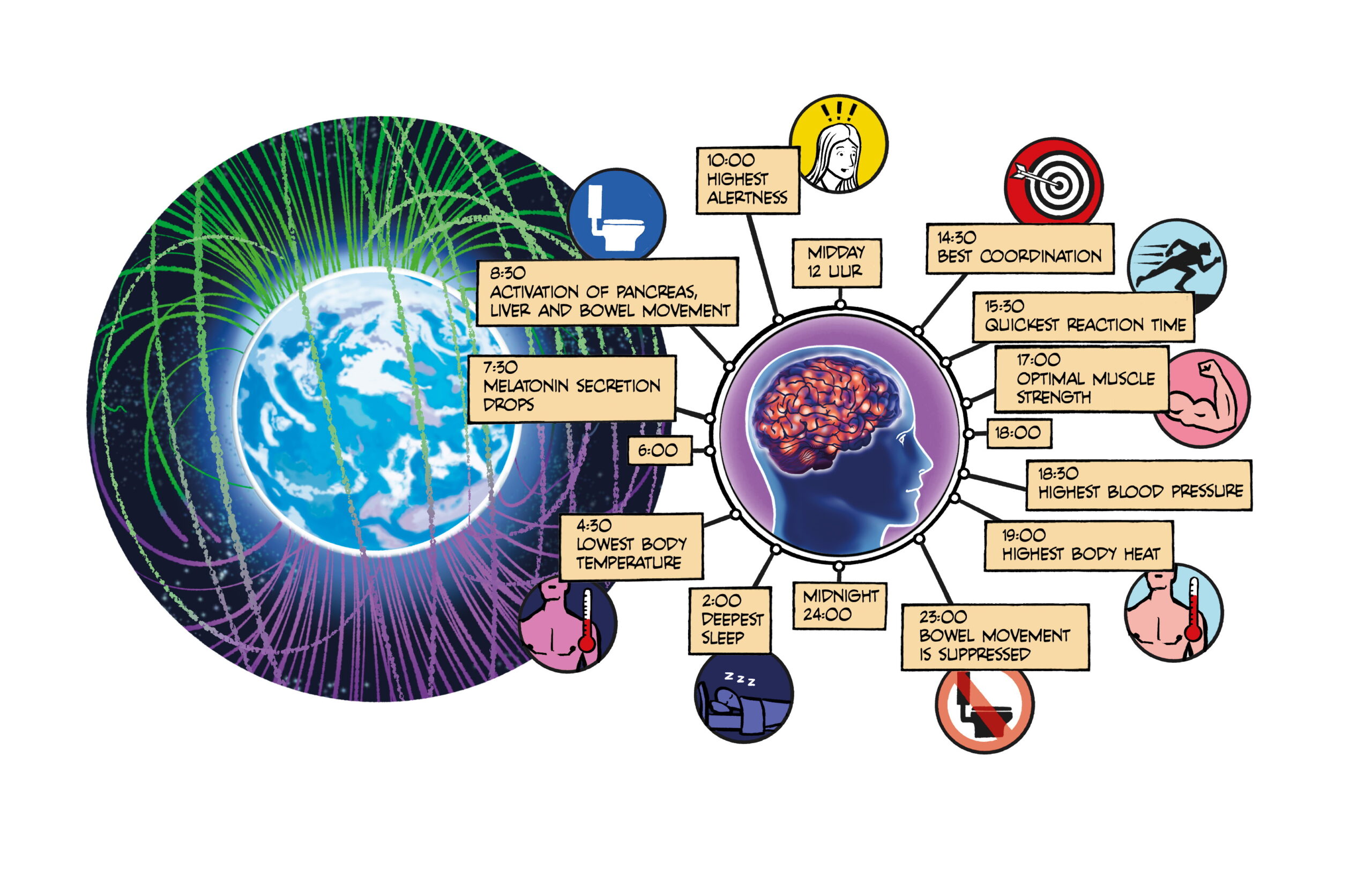

There are large clocks in nature that follow the sun’s input over the course of a decade. There are also smaller clocks that tune to the earth’s rotation, such as the circadian or biological rhythm of humans which lasts about 24 hours. This regulates the daily rhythm of all kinds of bodily processes: sleep and wake rhythms, hormones, body temperature, digestion, the immune system, blood circulation, blood pressure, emotions and the like.

This biological clock ticks in a brain area smaller than a pea. That is where our clock of clocks resides. And when that clock gets disturbed, that’s when things get messy.

About the clapper of the biological clock

When I was asked in late 2024 to evaluate Rütger Wever’s 1974 study “ELF-effects on human circadian rhythms”, I realized that circadian rhythms had been a blind spot in my life until then. I knew that the body is very fond of regularity and cycles, but I myself lived relatively ignorant of them. Without being aware of it at the beginning, my digging work into the aforementioned research began to change that attitude.

To be able to make the evaluation I began to delve, not only into the 50 years of research that had passed since Weaver, but also into all the other researches on biological rhythms from centuries before, since Jean-Jacques d’Ortous de Mairan first observed them in plants.

The Mimosa plant is not to be messed with

In the early eighteenth century, Jean-Jacques d’Ortous de Mairan played a crucial role in the very first discovery of biological rhythms. Although his work focused primarily on astronomy and atmospheric phenomena, a chance observation put him on the trail of one of the most intriguing properties of living organisms: circadian rhythms.

In 1729, De Mairan conducted a simple but revolutionary experiment. He observed the movements of the leaves of the Mimosa pudica (the sensitive plant or touch-me-not), known for its hypersensitivity to touch. The leaves of this plant close at night and open during the day. This fascinated De Mairan. He wondered if these movements were directly dependent on sunlight, or if there was an internal factor at play.

To test this, he placed a Mimosa plant in total darkness. To his surprise, the leaves continued to follow a pattern of opening and closing, as if they always “knew” by themselves when it was day or night. This suggested that the plant had an internal biological clock that functioned independently of external light signals.

Although De Mairan himself could not explain the cause of these rhythms, his research provided initial evidence for the idea that living organisms possess an internal clock that regulates their physiological processes. Later, these rhythms appeared not to be limited to plants as fungi, bacteria, birds, fish, other animals and humans were also found to use a variety of circadian rhythms.

Centuries later, Bengali researcher Sir Jagadish Chandra Bose accidentally stepped on a Mimosa plant. Surprised by the immediate folding of the plant’s leaves, he decided to learn more about plant behavior and their ways of communicating. He discovered that plants have an elaborate electrical conduction system and that there is a curious parallel between electrical transmissions in plants and in animals. He wrote a book about it in 1926, The Nervous Mechanism of Plants.

The independent control of the biological clock was called into question with the discoveries of Bose and others. The circadian rhythm of plants seemed to be controlled not only by light from the sun or solely by chemical processes inside the plants, but also by electrical input.

The question is not how much cheese we eat, but when

Every cell in the human body uses the biological clock. That means every cell can get upset when its rhythm is disrupted. This is certainly true for the clock in brain cells. The brain produces different substances during the day than it does at night. So when that clock gets upset, it affects the overall mood resulting in strange mood swings.

The biological clock also acts on the cells of the stomach and intestines. That clock determines what your body does with food. After 11 p.m., the work time of the intestines is over. That’s why eating late is one of the major causes of obesity; by midnight, the body no longer digests food. So a round of cheese cubes after midnight is unwise. It’s all a matter of timing.

The common thought is that through light influences from outside, the clock adjusts to the 24-hour rhythm. During the day, the body is full of energy but as soon as the sun goes down, the brain starts producing melatonin. The body becomes sleepy and body temperature and heart rate drop. In the morning, melatonin production stops and cortisol takes over. The body gets back on its feet. This makes flying to other time zones and nightshift work heavy, for example.

The immune system is regulated, among other things, by the TLR9 gene. This gene is also on the clock and not equally abundant at all times during the day. At night, it is much less present in the body than during the day. Therefore, we are much more susceptible to disease at night than during the day. For example, if you have partied through the night, the body thinks it is night during the day. As a result, you then have less TLR9 during the day – which would normally protect you from disease. Disrupting the biological clock however, has many other consequences. In fact, more than 90% of rhythmic genes become unbalanced during frequent nights of partying or working through until the early hours of the morning. So, the biological clock does not like night owls.

Back to the clapper: early to bed

So I learned something very important about the difference between what I like and what my body likes. At some point in the evaluation, it dawned upon me that this research would only become useful to me if I could do something practical with it.

As a New Year’s resolution, I decided to hang up my irregular sleep routine and give my body what it really asked for. How could I expect the complex tissue of fine-tuned systems, that makes up my body, to help me understand and evaluate circadian rhythms if I didn’t care about them!

From then on, I made sure I was in bed before the clock of 12 and began to explore at what times of the day I could best engage in what activities. This started the practicalities of that part of the research for me.

But there is another less familiar and less physical side to circadian rhythms. In fact, research into them has focused mainly on the idea that the biological clock is tuned to signals from the earth’s magnetic field.

Experiments underground

Rütger Wever was a German biologist and pioneer in the field of chronobiology. That is the study of biological rhythms and the internal clock of living organisms. Wever wondered what would happen to the biological clock of subjects in an environment without daylight, in which they were completely free to determine their own sleeping and waking rhythms. To do this, he used an underground bunker in Andechs, Germany. The subjects were shielded from the outside world and from the influence of the earth’s magnetic field. The absence of the influence of that field disturbed, among other things, the melatonin and cortisol cycle and the functioning of the pineal gland.

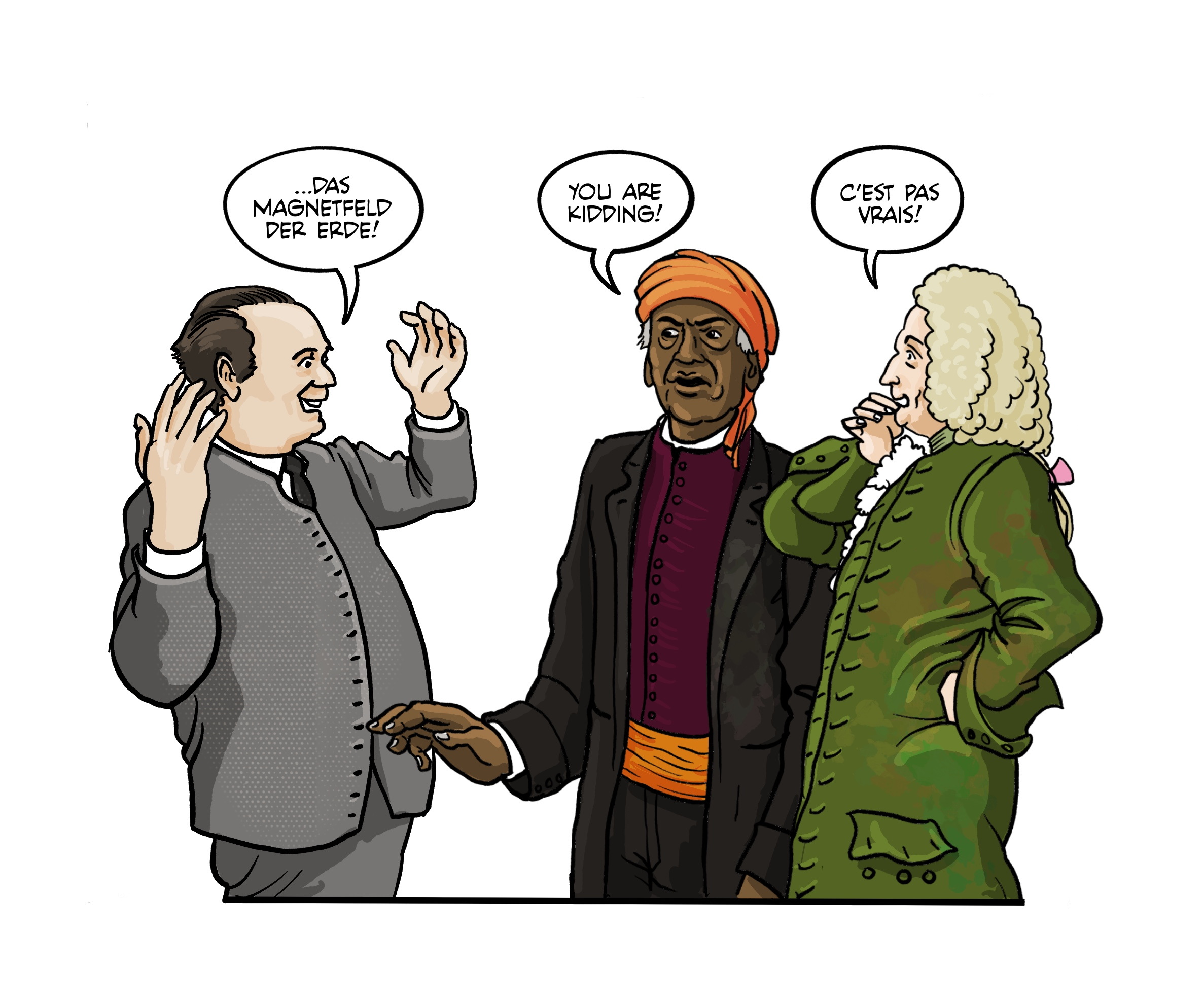

Rütger Wever, Sir Jagadish Chandra Bose and Jean-Jacques d’Ortous de Mairan

It soon became clear that the subjects’ circadian rhythms became confused. Some developed a slower rhythm than the usual 24 hours, while in others the rhythm actually speeded up. These irregularities led to subtle changes in the quality and duration of sleep, fluctuations in body temperature, increased stress sensitivity etc. The researcher’s conclusion; the geomagnetic field possibly acts as a kind of pacemaker for circadian rhythms.

And that which is true for the circadian rhythms of humans, also turns out to be true for those of monkeys, bees, turtles, fruit flies, pigeons, hamsters, dogs, cows, quails, gulls and mice, among others.

By the way, the result of a few months living in harmony with the biological clock, is actually quite surprising. In the first week after I started the experiment, I woke up often, felt restless at night and also found myself staring at the ceiling a lot. Pretty soon after that, these symptoms disappeared. The body seemed to adjust quite quickly to the new regularity, much faster than I had thought beforehand. Meanwhile, the body feels rested and vital at the beginning of the day, and during the day the energy seems to run out less quickly as well.

How electricity affects the genetic clock

In the 1980s, a few years after Wever’s research, scientists at Ciba Geigy initiated some mysterious experiments around the influence of electromagnetic waves on plant seeds. The techniques they used appeared capable of accelerating plant growth, strengthening crops and improving traits.

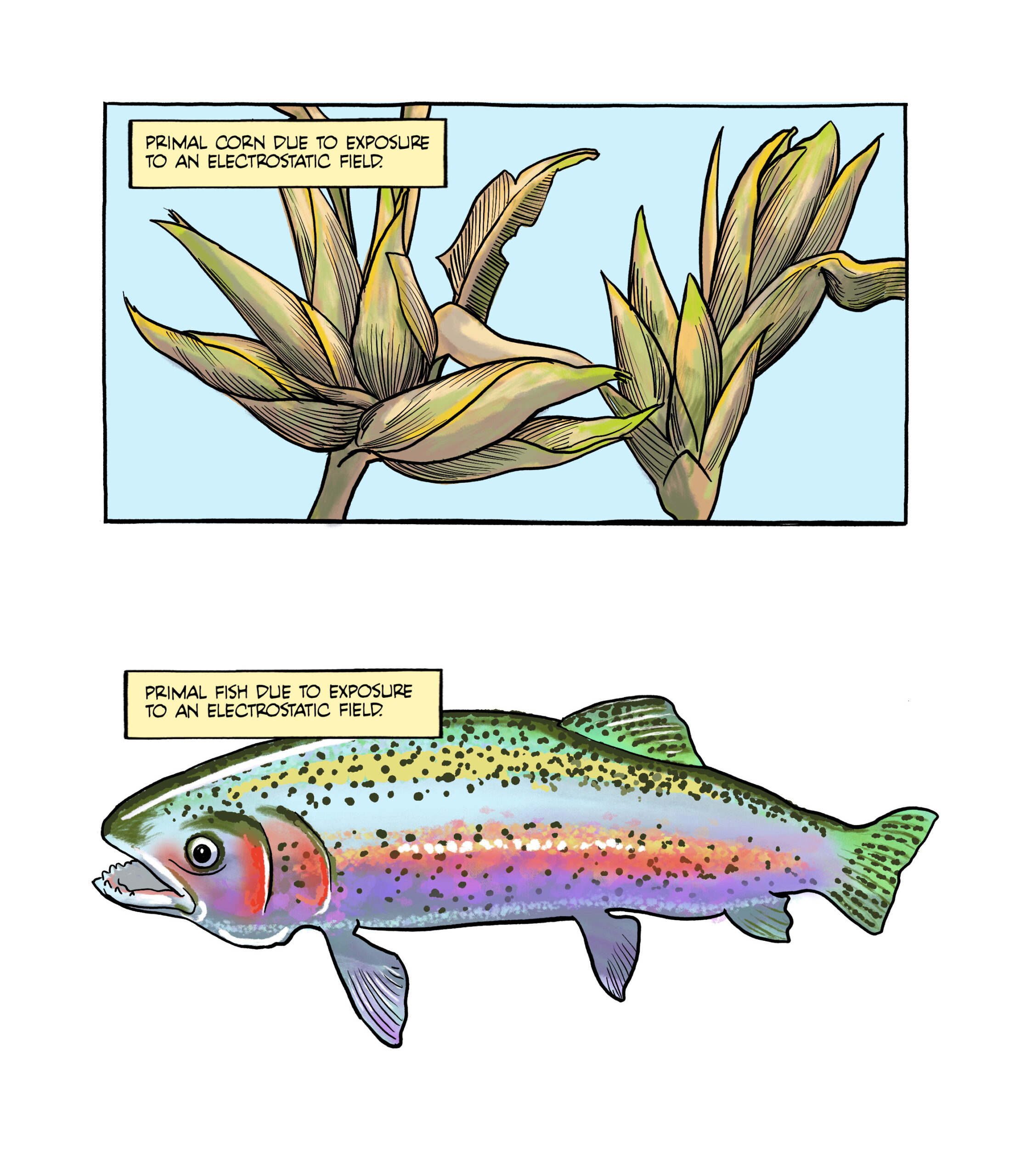

By amplifying the electric fields – of the same kind that the earth surrounds us with every day – the researchers were able to turn the genetic clock of plant seeds back to their original time. The seeds did not produce the same plants from which they had been harvested, but primal plants. The corn that grew from the seeds exposed to the fortified fields did not germinate into the corn plants as we know them today, but became primordial corn plants; an original species, from long before the time when humans genetically modified corn plants.

The same thing happened with fish eggs. Primal fish species emerged from eggs exposed to the amplified electric fields. Plants and fish that existed thousands of years ago, returned to the scientists’ test sites. So, specific electrostatic fields appear to have the ability to alter genetic codes and repair and restore primordial DNA..

The cosmic connection

On earth, the geomagnetic field regulates, among other things, people’s circadian rhythms. In space, it is a different story; the magnetic fields there, are different from those on earth. When space activities started in the late 1950s and early 1960s, astronauts’ biological clocks were found to be confused in space.

The brain has developed over millions of years under the influence of the ebb and flow of the earth’s magnetic field. The frequency patterns the brain works with are surprisingly similar to the frequency patterns of that field. That field not only affects the biological clock, but also influences brain waves. It mixes with our dreams, thoughts, feelings and emotions. Moreover, changes in the sun’s electrical activity also impact people’s circadian rhythms.

Thus, we appear to be connected in a deep, mysterious and profound way with the clocks ticking in a much larger context.

(This article was originally published in Dutch, in Optimist Magazine nr. 221, March/April 2025)

Sources of the biological clock